One of the highlights of this year's Ilkley Literature Festival was John Suchet discussing his new biography of Beethoven (http://www.amazon.co.uk/Beethoven-John-Suchet/dp/190764279X/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1353670265&sr=1-1). John Suchet is a journalist, news-reader, a presenter on Classic FM and acclaimed Beethoven scholar, having written six books about his favourite composer.

During his talk in Ilkley, John briefly discussed the ways that Beethoven had not only touched, but had saved people's lives. I am sure he is aware that the opening four notes of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony match the morse code for the letter 'V'. So it is understandable that, in the final days of World War Two, British radio broadcasts used these musical notes to reassure those in Europe living under Nazi occupation that victory was at hand, and members of the resistance movement began to paint the letter 'V' on walls throughout France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Beethoven was a major contributor in the psychological war.

In August 1991, the General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, Mikhail Gorbachev, was the victim of a brief and unsuccessful coup d'etat (the August Putsch or August Coup). The leaders of this putsch were hardline members of the Communist Party who opposed Gorbachev's programme of reform and liberalisation (Perestroika and Glasnost, two buzzwords that became familiar in the late 1980s). The coup collapsed after only two days and Gorbachev returned to the government.

As a shortwave radio fanatic and student of politics I monitored Radio Moscow World Service (RMWS) throughout the coup. In those days the station was not difficult to find: RMWS broadcast on all shortwave bandwidths and the number of frequencies it used outnumbered any other radio station. The station's identification which sounded before the news at the top of the hour was very familiar: the chimes of the Kremlin, followed by Midnight in Moscow and an announcer with a pseudo-American announcer reminding us that we were listening to Radio Moscow World Service.

(This is a RMWS programme schedule. I actually received on of these in return for sending them a reception report)

On 19 August 1991, the tone and content of programming changed, and broadcasts contained far less news and more silences and music. One piece of music that the station repeated over and over convinced me that RMWS was broadcasting a signal to its listeners - the coup would not succeed. That piece of music was Beethoven's Fifth Symphony with, in its opening bars, the distinctive morse code 'V' for victory. This was not the only signal. Those of us who obsessed about international radio broadcasting knew intimately the idiosyncrasies of each station. One unique characteristic of RMWS was that it only played music written by Russian composers, yet here it was at this dramatic and historic time playing the most famous work written by a German.

Of course it may all have been coincidental, the imaginings of a young mind convinced that shortwave radio broadcasts could and did play an important role in politics and international affairs (I was just starting my PhD research on this very topic). Yet I like to think that Radio Moscow World Service had made a conscious and strategic decision on that day - to use its power as a broadcaster to bypass the coup leaders and send a message to its listeners around the world: the coup will not succeed; everything is ok, and in the end it was - the putsch was defeated by popular resistance led by future Russian President, Boris Yeltsin, and by the disarray among the conspirators themselves. I also like to think that Beethoven played a small and significant role in the end of the coup and in the the dissolution of the Soviet Union as 1991 came to an end.

Thoughts and comments about public diplomacy, soft power and international communications by Gary Rawnsley.

Friday, 23 November 2012

Thursday, 22 November 2012

On Censorship

"All censorships exist to prevent anyone from challenging current conceptions and existing institutions. All progress is initiated by challenging current conceptions, and executed by supplanting existing institutions. Consequently, the first condition of progress is the removal of censorship." - George Bernard Shaw, Mrs Warren's Profession

"Withholding information is the essence of tyranny. Control of the flow of information is the tool of the dictatorship." - Bruce Coville

Censorship is the flipside to propaganda; it is incredibly difficult to succeed in the latter activity without paying due care and consideration to the former. After all, the selective use and dissemination of facts, information, news and opinion - all characteristics of propaganda - requires familiarity with censorship. I am surprised, however, that while the study of propaganda continues to attract academic attention, censorship has fared comparatively less well. Histories of propaganda, especially of the Nazi and Communist eras, and broader studies of warfare from World War One to the 2003 Iraq War, have naturally analysed the use of censorship. It is a recognised technique of persuasion used by governments and militaries, though like propaganda it is now used only as a pejorative label to signify the suppression of truth and accuracy.

However, as far as I know there is not a comprehensive study of the theory and practice of censorship, though I do hope that readers of this post will provide references to the literature I may have missed.

I am inspired to write about censorship after reading in the Observer newspaper (18 November 2012) a short article entitled 'How to turn damning press reviews into PR gold'. This refers to those moments in literature, theatre or film when 'Ambiguously phrased criticism is seized upon and passed off as possible praise'. The Observer article calls this 'Contextonomy'. So, one example:

Philip French, the Observer's film critic, on Anthony Page's 1979 remake of The Lady Vanishes:

Actual Quote: An amiable entertainment and about as necessary as a polystyrene version of the Taj Mahal. Hitchcock's 1938 comedy/thriller is a near-perfect artefact ... attaining a precise balance between suspense and laughter.

Quote Used by the film's marketing team: "Near-perfect ... a precise balance between suspense and laughter."

I use similar examples to teach my students about censorship. A bill-board outside a theatre may say 'Must see ...' when the critic actually wrote 'Must see to understand how incredibly bad this show really is.' There are no lies involved here, just the careful selection of facts; and by omitting information and context, these are good examples of censorship at work.

In studying, writing and talking about Chinese media and propaganda I am often faced with explaining how censorship works, even to the Chinese. The guide on my personal tour of CCTV in 2007 was anxious to show me the foreigners tapping away to produce copy. 'Look,' she exclaimed, 'no-one is standing over them looking over their shoulder.' Recently at a seminar in London, an employee at CCTV (not present at the seminar) had explained to a Professor of marketing that there is no censorship in CCTV; no-one tells the journalists what they can and cannot write, and no-one diligently checks their copy. I pointed out that censorship does not work like that - or at least, should not work like that - but then I was accused of perpetuating the stereotypes about Chinese communications and propaganda.

To be effective censorship must be subtle; it must go unnoticed. If the censorship is too obvious, then it loses its power. We are naturally curious creatures, and as the history of propaganda reveals to us time and time again, when audiences know that some information or news is being kept deliberately from them, they grow all the more determined to find out about it. When I am in China and BBC World's transmission on my hotel television suddenly disappears for thirty seconds, I know that the broadcast is being censored. Inevitably the question becomes: What is so interesting/dangerous/subversive that the Chinese censors feel the need to prevent me from seeing this item of news?

"To forbid us anything is to make us have a mind for it." - Michel de Montaigne.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the Chinese government’s blatant media censorship only whets the popular appetite for forbidden information. When Zhao Ziyang, to many a hero of the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations, died after fifteen years of house arrest in January 2005, the Chinese government controlled coverage of his passing and his funeral. Information was scarce: ‘I live in Guangzhou, and that night I wasn’t able to access two Hong Kong TV stations, so I realised immediately that something major had happened. …’; ‘ … today … my grandmother said, “Zhao Ziyang died, why isn’t the news or the papers reporting it?” I was curious, so I went searching on the Internet, but I found I couldn’t open many Web sites, which made me think something was strange. …’; ‘This morning, I couldn’t connect to any overseas web sites, and I realised that something had happened …’; ‘Putting aside Zhao’s merits and faults for the time being, we have already completely lost the right to speak, and to hear about him! What kind of world is this?’ (Emily Parker, “Cracks in the Chinese Wall,” The Asian Wall Street Journal,

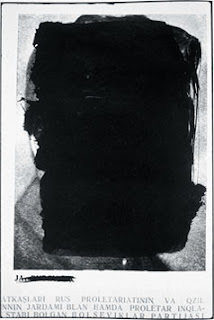

David King's wonderful collection of censored photographs from the Stalin era, The Commissar Vanishes (http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Commissar-Vanishes-David-King/dp/0805052941/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1353603294&sr=8-1), provides a whole book-full of examples of not-so-subtle censorship techniques.

As King's book shows, simply blacking out faces with ink or paint was a common method of censorship during Stalin's era in power.

Another example, this time from China. This photo was taken at the funeral of Mao Zedong in 1976 and shows the country's leadership lining up to pay their respects.

Spot the difference with the published version?

The so-called Gang of Four, including Mao's widow, all of whom were jailed (and some were executed) for their part in the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, were airbrushed from the official photo.

The Chinese - journalists and citizens writing on the internet - do find ways of circumscribing the official censorship architecture. A trawl through weibo, the Chinese twitter, reveals the code-words that users use to refer to otherwise sensitive topics, people and events. Journalists adopt strategies of self-censorship, and it is this that is a more worrying practice than overt forms of censorship. The laws on what can and cannot be said are so vague (I was told that there is no rule against talking about the Tiananmen Incident of 1989, but people just know you should not do it) that the perpetual climate of uncertainty prevents risk-taking.

However, it is clear that in an age of global media with information

immediately available to everyone with access to a computer – and despite the

Chinese government’s best attempts it is

possible to circumvent the Great Firewall - it is becoming less and less easy for governments

to manage information and the new public spaces that are materialising in

cyberspace. Michel Hockx is correct when he says that internet censorship ‘does

not necessarily confront Chinese writers and readers with an unfamiliar

situation. Censorship is the norm, rather than the exception.’[i]

But this should not and does not preclude value judgement of censorship or the possibility of change. Censorship may be ‘a fact of life’ and as observers we may be guilty of ‘foregrounding censorship’ which means ‘highlighting what does not appear on the Chinese internet’ and drawing attention away ‘from what does appear’.[ii] But the mechanisms of censorship reveal much about the architecture of government, elite opinion, and the perception of the power of communications. In accepting censorship as the norm we are in danger of overlooking one important detail: What is good for governance in China

While the old fashioned censorship of Stalin and post-Mao era China may have disappeared (though who needs ink and paint when you have photoshop?), censorship continues to be the tool of choice for some governments who wish to manage the flow of communication and information. Surely it is time for a new comprehensive study of its theory and practice?

[i] Michel Hockx, ‘Virtual Chinese

Literature: A Comparative Case Study of Online Poetry Communities’, in Culture

in Contemporary China Cambridge Cambridge University

[ii] Ibid, 149.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)