Few governments spend as much on their international outreach - what one might call 'soft power' - than China; and few governments get it wrong so spectacularly and so frequently. The main explanation for this lack of success is the failure to understand the first lesson of public diplomacy: Actions always speak louder than words; and that sometimes, saying or doing nothing is the most strategic course to take.

The discussion about how China's behaviour, at home and abroad, undermines its public diplomacy among the international community has a long history. The literature on China's soft power refers repeatedly to how China's record on human rights, democracy, the treatment of dissidents, and freedom of speech, as well as its behaviour towards Tibet and Xinjiang, challenge the more positive narratives that Beijing prefers to project in its international communication. And yet it seems that the Chinese government has difficulty in grasping that its response to adverse events and criticisms may also have negative consequences for its public diplomacy. In 2014 three events in just two months nurture this critical perspective.

The first event occurred in London on 4 June 2014, the 25th anniversary of the suppression by the People's Liberation Army of the protests in Beijing's Tiananmen Square. Two women, one of whom was Wang Ti-Anna, the daughter of a democracy activist, were shoved away from the Chinese embassy in London by staff who also threw to the ground the flowers the two women wished to leave on the steps ... and this happened in front of television news cameras from across the world. This not only indicates that staff in the embassy fail to understand how public diplomacy works - do not react in ways that will inflame the situation and give journalists the story they seek; if in doubt say and do nothing - but it also suggests that embassy staff had to be seen, by their superiors inside the building or in Beijing, to be doing something, even if it results in bad publicity. You can see the BBC's footage of the event here: Chinese embassy in London

A second related event occurred on 18th August 2014. Clive Palmer, a member of the Australian Parliament, launched a tirade on live television against China and the Chinese. His vile, offensive and racist language has been reported all around the world and has given Palmer more international publicity than he deserves. The Chinese embassy in Canberra should have been advised to issue a statement condemning Palmer and his remarks, but reassuring Australians that the Chinese government recognises he was not speaking for all Australians; that Australia remains an important and friendly country to China; and that relations would not be disrupted by the inanity of one man's comments. That is diplomacy. Instead, China's state-owned newspaper, the Global Times, decided to respond in its English language edition with its own excessive zeal, claiming that Palmer 'serves as a symbol that Australian society has an unfriendly attitude towards China'. The editorial continued by recommending that Australia 'must be marginalized in China's global strategy'. Again such ill-advised rhetoric only inflames further the situation, demonstrates that China's public diplomacy is neither as sophisticated nor as sensitive as Beijing would like to think, and shows yet again that China is unable to respond in a rational way to criticism. Rather, the government decided to generalise about a whole country from the ramblings of one man, something the Chinese repeatedly accuse westerners of doing about China. Clearly the Chinese government and its embassies need better advice on how to handle the international media. You can see Palmer's outburst here: Clive Palmer and read the Global Times article here Global Times.

The third event is more sinister and perhaps undermines China's soft power more than the other two incidents put together. On 22 July 2014 at the annual conference of the European Association for Chinese Studies in Portugal, China's Vice-Minister Xu Lin, Director-General of the Confucius Institutes, impounded all copies of the conference programme and refused to release them until organisers removed pages she deemed offensive. What was so distasteful for Xu was an acknowledgement in the programme that part of the conference was sponsored by Taiwan's Chiang Ching-kuo (CCK) Foundation. Several pages including an advertisement for the CCK Foundation were ripped from a programme which the Confucius Institute had no role in funding. In a published statement (statement) the President of the EACS, Roger Greatrex, said: 'Providing support for a conference does not give any sponsor the right to dictate parameters to academic topics or to limit open academic presentation and discussion, on the basis of political requirements'. At a time when the role of Confucius Institutes - long celebrated as a shining example of China's public and cultural diplomacy - is being scrutinised closely and debated across the world, but especially in the US, Xu Lin could not have picked a worse time to assert her imaginary authority. It is not surprising that headlines in western media adopted critical, sometimes hostile language in reporting and commenting on this news: "Censorship at the China Studies Meeting" (Inside Higher Education); "China fails the soft power test" (China Spectator); "Beijing's Propaganda Lessons: Confucius Institute officials are agents of Chinese censorship" (Wall Street Journal). Academic institutions will now have reason to be more suspicious of Confucius Institutes, while those who have long suspected their political agenda will have far more credibility.

The lesson here for China is very clear: Think before you speak; think before you act. What you do in response to something that you may find unfavourable or even offensive may backfire and ultimately undermine the credibility of your soft power campaign. When in doubt, say and do nothing.

Thoughts and comments about public diplomacy, soft power and international communications by Gary Rawnsley.

Showing posts with label censorship. Show all posts

Showing posts with label censorship. Show all posts

Wednesday, 20 August 2014

Thursday, 18 July 2013

King Canute versus the tide

Twenty years ago, when I was a naïve but ambitious 23 year old second-year student in the final stages of my PhD, I embarked on the hunt for my first academic position. Since being a teenager besotted by the world of shortwave radio international broadcasting my work has always been located at the intersection of international politics and communications. I was convinced then, and remain so today that it is impossible to discuss politics and international politics in any meaningful way without also understanding the role of communications, information and the media. Despite the war against Iraq in 1991 (Gulf War I or II? Surely the Iran-Iraq conflict was the first Gulf War?) and the advent of 24/7 live broadcasting from the front which had a profound impact on how the war played out - and introduced the CNN Effect which suggests foreign policy can be driven by media coverage and popular opinion - I still met a shocking amount of resistance in reputable politics departments where earnest academics dismissed such work as Mickey Mouse studies. Such ignorance.

Fast forward twenty years and, despite the Internet and social media having transformed political processes and empowered millions of people across the world; despite the acceptance by all governments that public diplomacy and the exercise of soft power are essential tools of statecraft; despite militaries begging us to teach them how to adapt to, and survive in the information age; despite governments trying to find innovative ways to manage the public and private conversations their people are having, while some are resorting to good-old fashioned techniques of censorship to control access to information; and despite communications panels almost taking over the major academic conferences in politics and international relations, we are still facing denigration by academics who refuse to see the essential and fundamental impact that communications have upon political events, institutions, agents and processes. Satellite broadcasting, the rise of pan-regional media organisations like Al-Jazeera, citizen journalism, tweets, blogs, Facebook and social networking have all transformed the way governments and militaries speak to journalists and audiences, and how publics speak to each other.

It is sad that the ignorance I encountered twenty years ago persists. As recently as last year I was again told that my work is not considered 'mainstream', whatever that means anymore. I also remember my intervention at a conference last year when I realised how my work on communication can undermine the more militaristic approach to international relations that prefers to kill and maim human beings rather than persuade them that there might be alternatives to hard power (A note so subtle reminder ...). As Joseph Nye wrote, militaries (and too many academics working in IR and security studies) prefer 'something that could be dropped on your foot or on your cities, rather than something that might change your mind about wanting to drop anything in the first place' (Nye, 2011: 82).

Consider the events of 11th September 2001 when audiences were led to believe they watched the horror of 9/11 unfold live on their television screens. However, it is only by sheer luck that we have any footage of the first hijacked plane hitting the North Tower of the World Trade Centre WTC) at 8:46 am local time. In the neighbourhood were filmmakers James Hanlon and the Naudet brothers making a documentary about a probationary New York fireman. When American Airlines Flight 11 flew by, Jules Naudet turned his camera to follow the plan and taped only one of three know recordings of the first plane hitting the WTC (the others being a video postcard by Pavel Hlava filming a visit to New York to send home to family in the Czech Republic, and a sequence of still frame CCTV photographs by artist Wolfgang Staehle). In this way, the biggest and most momentous news event of recent decades was captured and recorded by 'accidental journalists' who just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Seventeen minutes later at 9:03 am, a second plane hit the WTC's South Tower. This time the collision was broadcast live on television, captured by professional camera crews circulating the burning North Tower in helicopters. The level of media literacy within Al-Qaeda had been demonstrated very clearly: the organisers of the hijacking knew that the first collision would not be reported live, do delayed the second attack to generate media interest and coverage. In this way, the events of 9/11 confirmed that the media, communications and information landscapes had changed beyond recognition, and they continue to change.

The power of information since 9/11 and during the inappropriately named War on Terror has not been overlooked. In 2007, US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates noted, 'It is just plain embarrassing that Al-Qaeda is better at communicating its message on the Internet than America. Speed, agility, and cultural relevance are not terms that come readily to mind when discussing US strategic communications.' Gates recalled how one US diplomat had asked him, 'How has one man in a cave managed to out-communicate the world's greatest communication society?' Four years later, Washington's political elite were still pondering the US's incapacity to compete in the communication landscape: In March 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton admitted in testimony to the Senate's Foreign Affairs Committee that 'We are in an information war and we are losing that war.' It seems that policy-makers, unlike many academics, recognise the urgent need to understand how communications, the media, politics and strategy are now permanently entwined.

I was reminded of these issues last night when I watched at the local cinema a wonderful documentary called We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks (2013, dir. Alex Gibney). Anyone who is still blinkered to the effect of communications on political processes and institutions should see this film. At its core is the belief that information is power, and that withholding the publication of information is a political act designed to serve a specific political agenda. Anyone with any understanding of basic politics will uncover in this film issues about authority, transparency, legitimacy, accountability, political ethics, the appropriate level of force in war, national security and fundamental questions about democracy; and all these issues are framed against the transformation of private and public space by the media and new communications technologies. The film, and the whole Wikileaks saga in general - just like the recent revelations about GCHQ's use of the PRISM surveillance data - provides a valuable case-study for students trying to unravel the theoretical and empirical complexity of modern politics. It compels us to confront difficult philosophical questions, and come to terms with the somewhat uncomfortable realisation that there is no right or wrong; no black and white, just gradations of murky grey. Adrian Lamo, the hacker who turned-in Bradley Manning to the authorities at the height of the Wikileaks story, even justified his actions in classic utilitarian terms: the good of the many outweighed the good of the few, or in this case, the one. (Discuss.). What an exciting way to stimulate students' interest in normative ethics. Moreover, we are compelled to think about and test the boundaries of what is and is not permissible in the new communications ecology: What do we mean by freedom of speech? Who has responsibility for what is posted on the internet and the consequences for doing so? Who decides what is and is not acceptable, why and by what criteria? I short, the modern communications landscape calls for a (re)consideration of the most basic of political questions: What is power, and how is power distributed and exercised?

Academics who continue to deny that communications and the media are at the heart of modern 'mainstream' debates about politics are like King Canute trying to hold back the tide. Real-world politics have moved on; it is a shame that there are still academics who refuse to accept it.

[Mr Justice Openshaw, a Crown Court judge in Woolwich, UK, presiding over the trial in May 2007 of three young Muslims accused of distributing propaganda over the internet in support of Al-Qaeda, confessed during the proceedings: 'The trouble is I don't understand the language. I don't really understand what a website is.' The judge then 'paid close attention as Professor Tony Sams, a computer expert, explained in detail how the internet works'.

'What's a website, asks judge at internet trial,' The Telegraph, 18 May 2007]

Fast forward twenty years and, despite the Internet and social media having transformed political processes and empowered millions of people across the world; despite the acceptance by all governments that public diplomacy and the exercise of soft power are essential tools of statecraft; despite militaries begging us to teach them how to adapt to, and survive in the information age; despite governments trying to find innovative ways to manage the public and private conversations their people are having, while some are resorting to good-old fashioned techniques of censorship to control access to information; and despite communications panels almost taking over the major academic conferences in politics and international relations, we are still facing denigration by academics who refuse to see the essential and fundamental impact that communications have upon political events, institutions, agents and processes. Satellite broadcasting, the rise of pan-regional media organisations like Al-Jazeera, citizen journalism, tweets, blogs, Facebook and social networking have all transformed the way governments and militaries speak to journalists and audiences, and how publics speak to each other.

It is sad that the ignorance I encountered twenty years ago persists. As recently as last year I was again told that my work is not considered 'mainstream', whatever that means anymore. I also remember my intervention at a conference last year when I realised how my work on communication can undermine the more militaristic approach to international relations that prefers to kill and maim human beings rather than persuade them that there might be alternatives to hard power (A note so subtle reminder ...). As Joseph Nye wrote, militaries (and too many academics working in IR and security studies) prefer 'something that could be dropped on your foot or on your cities, rather than something that might change your mind about wanting to drop anything in the first place' (Nye, 2011: 82).

Consider the events of 11th September 2001 when audiences were led to believe they watched the horror of 9/11 unfold live on their television screens. However, it is only by sheer luck that we have any footage of the first hijacked plane hitting the North Tower of the World Trade Centre WTC) at 8:46 am local time. In the neighbourhood were filmmakers James Hanlon and the Naudet brothers making a documentary about a probationary New York fireman. When American Airlines Flight 11 flew by, Jules Naudet turned his camera to follow the plan and taped only one of three know recordings of the first plane hitting the WTC (the others being a video postcard by Pavel Hlava filming a visit to New York to send home to family in the Czech Republic, and a sequence of still frame CCTV photographs by artist Wolfgang Staehle). In this way, the biggest and most momentous news event of recent decades was captured and recorded by 'accidental journalists' who just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Seventeen minutes later at 9:03 am, a second plane hit the WTC's South Tower. This time the collision was broadcast live on television, captured by professional camera crews circulating the burning North Tower in helicopters. The level of media literacy within Al-Qaeda had been demonstrated very clearly: the organisers of the hijacking knew that the first collision would not be reported live, do delayed the second attack to generate media interest and coverage. In this way, the events of 9/11 confirmed that the media, communications and information landscapes had changed beyond recognition, and they continue to change.

The power of information since 9/11 and during the inappropriately named War on Terror has not been overlooked. In 2007, US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates noted, 'It is just plain embarrassing that Al-Qaeda is better at communicating its message on the Internet than America. Speed, agility, and cultural relevance are not terms that come readily to mind when discussing US strategic communications.' Gates recalled how one US diplomat had asked him, 'How has one man in a cave managed to out-communicate the world's greatest communication society?' Four years later, Washington's political elite were still pondering the US's incapacity to compete in the communication landscape: In March 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton admitted in testimony to the Senate's Foreign Affairs Committee that 'We are in an information war and we are losing that war.' It seems that policy-makers, unlike many academics, recognise the urgent need to understand how communications, the media, politics and strategy are now permanently entwined.

I was reminded of these issues last night when I watched at the local cinema a wonderful documentary called We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks (2013, dir. Alex Gibney). Anyone who is still blinkered to the effect of communications on political processes and institutions should see this film. At its core is the belief that information is power, and that withholding the publication of information is a political act designed to serve a specific political agenda. Anyone with any understanding of basic politics will uncover in this film issues about authority, transparency, legitimacy, accountability, political ethics, the appropriate level of force in war, national security and fundamental questions about democracy; and all these issues are framed against the transformation of private and public space by the media and new communications technologies. The film, and the whole Wikileaks saga in general - just like the recent revelations about GCHQ's use of the PRISM surveillance data - provides a valuable case-study for students trying to unravel the theoretical and empirical complexity of modern politics. It compels us to confront difficult philosophical questions, and come to terms with the somewhat uncomfortable realisation that there is no right or wrong; no black and white, just gradations of murky grey. Adrian Lamo, the hacker who turned-in Bradley Manning to the authorities at the height of the Wikileaks story, even justified his actions in classic utilitarian terms: the good of the many outweighed the good of the few, or in this case, the one. (Discuss.). What an exciting way to stimulate students' interest in normative ethics. Moreover, we are compelled to think about and test the boundaries of what is and is not permissible in the new communications ecology: What do we mean by freedom of speech? Who has responsibility for what is posted on the internet and the consequences for doing so? Who decides what is and is not acceptable, why and by what criteria? I short, the modern communications landscape calls for a (re)consideration of the most basic of political questions: What is power, and how is power distributed and exercised?

Academics who continue to deny that communications and the media are at the heart of modern 'mainstream' debates about politics are like King Canute trying to hold back the tide. Real-world politics have moved on; it is a shame that there are still academics who refuse to accept it.

[Mr Justice Openshaw, a Crown Court judge in Woolwich, UK, presiding over the trial in May 2007 of three young Muslims accused of distributing propaganda over the internet in support of Al-Qaeda, confessed during the proceedings: 'The trouble is I don't understand the language. I don't really understand what a website is.' The judge then 'paid close attention as Professor Tony Sams, a computer expert, explained in detail how the internet works'.

'What's a website, asks judge at internet trial,' The Telegraph, 18 May 2007]

References

Joseph Nye (2011), The Future of Power (New York: PublicAffairs).

Thursday, 22 November 2012

On Censorship

"All censorships exist to prevent anyone from challenging current conceptions and existing institutions. All progress is initiated by challenging current conceptions, and executed by supplanting existing institutions. Consequently, the first condition of progress is the removal of censorship." - George Bernard Shaw, Mrs Warren's Profession

"Withholding information is the essence of tyranny. Control of the flow of information is the tool of the dictatorship." - Bruce Coville

Censorship is the flipside to propaganda; it is incredibly difficult to succeed in the latter activity without paying due care and consideration to the former. After all, the selective use and dissemination of facts, information, news and opinion - all characteristics of propaganda - requires familiarity with censorship. I am surprised, however, that while the study of propaganda continues to attract academic attention, censorship has fared comparatively less well. Histories of propaganda, especially of the Nazi and Communist eras, and broader studies of warfare from World War One to the 2003 Iraq War, have naturally analysed the use of censorship. It is a recognised technique of persuasion used by governments and militaries, though like propaganda it is now used only as a pejorative label to signify the suppression of truth and accuracy.

However, as far as I know there is not a comprehensive study of the theory and practice of censorship, though I do hope that readers of this post will provide references to the literature I may have missed.

I am inspired to write about censorship after reading in the Observer newspaper (18 November 2012) a short article entitled 'How to turn damning press reviews into PR gold'. This refers to those moments in literature, theatre or film when 'Ambiguously phrased criticism is seized upon and passed off as possible praise'. The Observer article calls this 'Contextonomy'. So, one example:

Philip French, the Observer's film critic, on Anthony Page's 1979 remake of The Lady Vanishes:

Actual Quote: An amiable entertainment and about as necessary as a polystyrene version of the Taj Mahal. Hitchcock's 1938 comedy/thriller is a near-perfect artefact ... attaining a precise balance between suspense and laughter.

Quote Used by the film's marketing team: "Near-perfect ... a precise balance between suspense and laughter."

I use similar examples to teach my students about censorship. A bill-board outside a theatre may say 'Must see ...' when the critic actually wrote 'Must see to understand how incredibly bad this show really is.' There are no lies involved here, just the careful selection of facts; and by omitting information and context, these are good examples of censorship at work.

In studying, writing and talking about Chinese media and propaganda I am often faced with explaining how censorship works, even to the Chinese. The guide on my personal tour of CCTV in 2007 was anxious to show me the foreigners tapping away to produce copy. 'Look,' she exclaimed, 'no-one is standing over them looking over their shoulder.' Recently at a seminar in London, an employee at CCTV (not present at the seminar) had explained to a Professor of marketing that there is no censorship in CCTV; no-one tells the journalists what they can and cannot write, and no-one diligently checks their copy. I pointed out that censorship does not work like that - or at least, should not work like that - but then I was accused of perpetuating the stereotypes about Chinese communications and propaganda.

To be effective censorship must be subtle; it must go unnoticed. If the censorship is too obvious, then it loses its power. We are naturally curious creatures, and as the history of propaganda reveals to us time and time again, when audiences know that some information or news is being kept deliberately from them, they grow all the more determined to find out about it. When I am in China and BBC World's transmission on my hotel television suddenly disappears for thirty seconds, I know that the broadcast is being censored. Inevitably the question becomes: What is so interesting/dangerous/subversive that the Chinese censors feel the need to prevent me from seeing this item of news?

"To forbid us anything is to make us have a mind for it." - Michel de Montaigne.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the Chinese government’s blatant media censorship only whets the popular appetite for forbidden information. When Zhao Ziyang, to many a hero of the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations, died after fifteen years of house arrest in January 2005, the Chinese government controlled coverage of his passing and his funeral. Information was scarce: ‘I live in Guangzhou, and that night I wasn’t able to access two Hong Kong TV stations, so I realised immediately that something major had happened. …’; ‘ … today … my grandmother said, “Zhao Ziyang died, why isn’t the news or the papers reporting it?” I was curious, so I went searching on the Internet, but I found I couldn’t open many Web sites, which made me think something was strange. …’; ‘This morning, I couldn’t connect to any overseas web sites, and I realised that something had happened …’; ‘Putting aside Zhao’s merits and faults for the time being, we have already completely lost the right to speak, and to hear about him! What kind of world is this?’ (Emily Parker, “Cracks in the Chinese Wall,” The Asian Wall Street Journal,

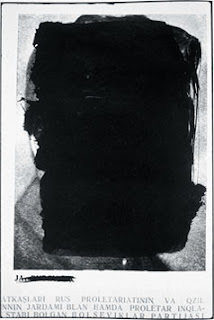

David King's wonderful collection of censored photographs from the Stalin era, The Commissar Vanishes (http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Commissar-Vanishes-David-King/dp/0805052941/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1353603294&sr=8-1), provides a whole book-full of examples of not-so-subtle censorship techniques.

As King's book shows, simply blacking out faces with ink or paint was a common method of censorship during Stalin's era in power.

Another example, this time from China. This photo was taken at the funeral of Mao Zedong in 1976 and shows the country's leadership lining up to pay their respects.

Spot the difference with the published version?

The so-called Gang of Four, including Mao's widow, all of whom were jailed (and some were executed) for their part in the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, were airbrushed from the official photo.

The Chinese - journalists and citizens writing on the internet - do find ways of circumscribing the official censorship architecture. A trawl through weibo, the Chinese twitter, reveals the code-words that users use to refer to otherwise sensitive topics, people and events. Journalists adopt strategies of self-censorship, and it is this that is a more worrying practice than overt forms of censorship. The laws on what can and cannot be said are so vague (I was told that there is no rule against talking about the Tiananmen Incident of 1989, but people just know you should not do it) that the perpetual climate of uncertainty prevents risk-taking.

However, it is clear that in an age of global media with information

immediately available to everyone with access to a computer – and despite the

Chinese government’s best attempts it is

possible to circumvent the Great Firewall - it is becoming less and less easy for governments

to manage information and the new public spaces that are materialising in

cyberspace. Michel Hockx is correct when he says that internet censorship ‘does

not necessarily confront Chinese writers and readers with an unfamiliar

situation. Censorship is the norm, rather than the exception.’[i]

But this should not and does not preclude value judgement of censorship or the possibility of change. Censorship may be ‘a fact of life’ and as observers we may be guilty of ‘foregrounding censorship’ which means ‘highlighting what does not appear on the Chinese internet’ and drawing attention away ‘from what does appear’.[ii] But the mechanisms of censorship reveal much about the architecture of government, elite opinion, and the perception of the power of communications. In accepting censorship as the norm we are in danger of overlooking one important detail: What is good for governance in China

While the old fashioned censorship of Stalin and post-Mao era China may have disappeared (though who needs ink and paint when you have photoshop?), censorship continues to be the tool of choice for some governments who wish to manage the flow of communication and information. Surely it is time for a new comprehensive study of its theory and practice?

[i] Michel Hockx, ‘Virtual Chinese

Literature: A Comparative Case Study of Online Poetry Communities’, in Culture

in Contemporary China Cambridge Cambridge University

[ii] Ibid, 149.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)